This is from 2012 | 5 minute read

Going Public, and The Pursuit of Quarterly Profits

These are some of the common reasons why a company goes public:

- To raise capital for new product development, acquisitions, or large expenditures like new buildings

- To reward employees for their work

- To provide a way for investors to make their expected returns

- To compensate founders

But when a company has publically traded stock, there are suddenly new constraints placed on the business. The company now needs to continually earn more money, per quarter, than they earned the previous quarter. That sounds like a good goal—more wealth, more opportunity—but it introduces a completely arbitrary duration for done-ness. 3 months is now the timespan for doing and assessing. If earnings are to be reported each quarter, then activities that promote earnings should fit nicely into 3 month increments. Actions are taken to remedy poor earnings, such as reorgs and layoffs, but these are taken as a response to this 3 month window and not to the response of actual product successes. The potential for long and lasting vision becomes difficult, if not impossible, by the constant need for predictable, financial growth.

Consider HP's recent announcement to cut 30,000 jobs, and ask yourself—how does a company get in a position where they need to eliminate 30,000 jobs all at once? If this was a change in strategy, it must be a pretty massive change ("Let's make cars instead of computers"); if it was based on suddenly knowing something they didn't know before, that speaks pretty poorly for their internal knowledge sharing ("Wow, turns out that our printer division sucks"). It's not based on any of these things; it's based on a response to the quarterly outlook of the company.

"Ms. Whitman came to the helm promising to return money to shareholders, and then set H.P. on a course for growth. To date, she has raised H.P.'s stock dividend, and in March announced a corporate reorganization intended to consolidate operational efficiency, for example by merging the PC and printer businesses." [source] The company has 324,000 people (that's nearly half the size of Austin), and generated $7 billion dollars in profit in 2011. By any standards that make sense, that's big enough and lucrative enough. But in the crazy game of publically traded companies, that's neither big enough nor profitable enough. Because the goal is not profit: it's more profit than three months ago. Till when? Till forever. And that's where the whole house of cards comes crashing down. Because there are only a handful of ways to make more profit than before, till forever, in three month increments. In order of increasing ethical questionability, you can:

- trim inefficiencies

- keep making new products and services that people find necessary to buy

- acquire companies

- license your IP to other people

- sue other companies

- fire people

- lobby the government to create legislation in your favor

- monetize your product through advertising

I find the push towards advertising a tell, a signal to the world that "we couldn't figure out how to make any of the other, less obtuse ways of creating value work, so we've sold ourselves out to the highest bidder." I'll offer you three examples of companies that have arrived at the bottom of the "we're now public, and so we're essentially screwed" profit-generation game.

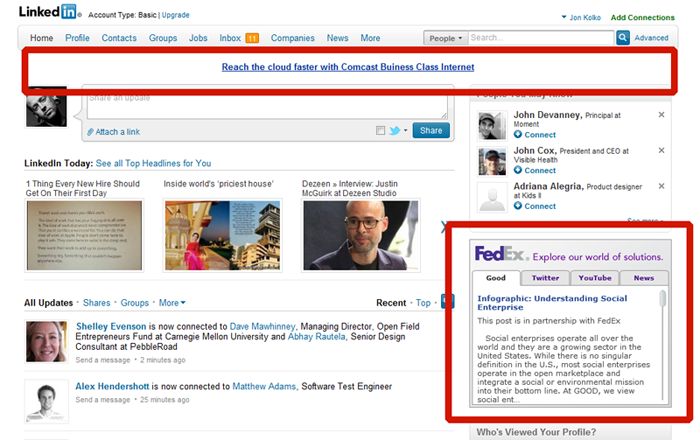

Linked In:

In addition to the advertising that's all over Linked In, you'll start to see a more pervasive push for you to sign up for a paid account. For example, you can now only view the full name of first and second connections, unless you upgrade:

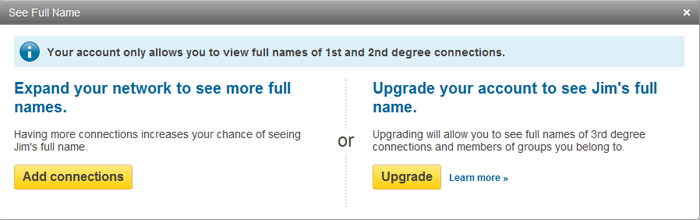

Monster:

Nearly half of Monster's product is devoted to serving up ads, and when you register, you can expect your data to be sold to everyone on the planet.

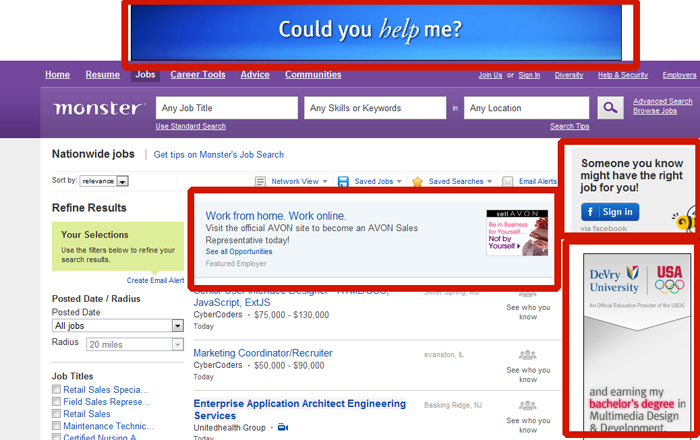

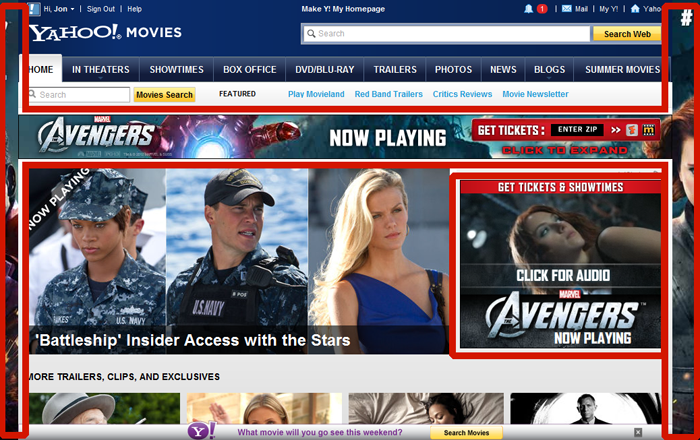

Yahoo!:

I can't tell what's an ad and what isn't, and that is, of course, the point. Just please, click anywhere and we'll make a few cents. Anywhere. Please.

*

We're increasingly seeing calls for companies to reign in the relentless push for quarterly profits. The Henry Jackson Initiative for Inclusive Capitalism (or HJIfIC) has described that "Compensation decisions taken in relation to short-term criteria have not reflected the long-term interests of the companies concerned." This is true. (The follow-up line is sort of a kick in the teeth, as their conclusion is not that companies should focus on long-term profits because it's healthier and maintains a greater pride in producing quality products, but instead, "Cases such as these erode popular support for capitalism.") Al Gore is pushing for a long-view. And Jeff Bezos is commonly referenced as an indicator of the importance of patience in the long view, although I'm not the first to point out that Amazon's home page looks like someone threw up all over it.

Over the next six months, facebook will start to undergo a subtle change, as benchmarks are set for quarterly profits and revenue targets start to slip. You'll begin seeing advertising in more prominent places, encroaching on the heart and soul of the product itself. And then, one day, most people will stop using facebook altogether, because another platform will have emerged that hasn't yet polluted their product with advertising, hasn't crammed as many sponsored deals into one page, hasn't started to nickel and dime users through premium features. It isn't going to be lack of innovation that pushes people to leave facebook. It's going to be their now and forever pursuit of quarterly profits.

Originally posted on Sat, 19 May 2012