This is from 2022 | 8 minute read

Enough Design Methods

A method is a way to do something that’s standardized, repeatable, structured, and systematic. And methods run counter to the ethos of creativity, the magic of making something from nothing.

Design firm IDEO published 51 method cards intended to “encourage you to try new approaches for making design useful, usable, and delightful to people.”

The d.school, a part of Stanford, published 37 methods in their “bootcamp bootleg,” which outline “each mode of a human-centered design process, and then describe dozens of specific methods to do design work.”

frog design, where I used to work, has a “collective action toolkit” with 30 methods that enable “groups of people anywhere to organize, collaborate, and create solutions for problems affecting their community.”

IBM has their IBMDT method cards. 18F, a government agency focused on design, has human-centered design method cards. Cooper has cards. SAP has cards. And on and on.

Designers are enamored with methods that define “ways of designing” and there’s an historical backstory to this. In the 1960s and ’70s, the United States and England were riding on the back of the scientific progress of the ’50s, particularly in the space of consumerism, urban planning, and architecture. There was a strong effort to make fields like industrial design and planning more scientific, more methodical, rational, predictable, and repeatable. Much of this was captured in a movement called the “design methods movement” spearheaded by Christopher Alexander.

Alexander has become known for his work in pattern languages, adopted by computer scientists. But in the late ’60s and early ’70s, his work focused more on discrete and formal ways of doing things–mathematical ways to solve human design problems. He popularized the idea that there’s a “right way” to design with an optimal process that arrives at the best results. Consider the housing projects of that time: top down, autocratic approaches to creatively solving difficult problems like affordable housing. It makes historic sense that architects wanted to improve the world around them by providing housing en masse for people in need.

The idea of optimal solutions was echoed by Herb Simon, an early pioneer in the field of artificial intelligence, who dedicated his career to understanding how humans solve problems in order to teach computers to do the same. He described the way designers use a hierarchical form of subdivision to continually break down systems into smaller and smaller components. In the same way that science has a way of deciphering natural phenomena, he argued that design too could explain (and produce) human-made phenomena through topics like economics or culture.

Methods reinforce that we are in control and can tame the complex world around us. Employing this rigorous approach adds a sense of sophistication to design activities, separating them from art–a discipline with a reputation for being less serious or important–and elevating the perception and value of design in the eyes of business and government.

But time has shown that a top-down approach to design activities frequently results in failure–the housing projects mentioned above are one of the most obvious examples. Instead of creating a perfect living arrangement, the mandated mini-city became a segregated urban ghetto and created a very clear delineation between haves and have nots, largely based on race. We designers were unable to “science” our way to a clear and concise solution because our systems include people, and people don’t behave according to top-down rules. They behave in irrational ways, causing the system to operate in strange, unintended ways.

Alexander recognized this and eventually rejected the entire movement, declaring “I have been hailed as one of the leading exponents of these so-called design methods. I am very sorry that this has happened, and want to state, publicly, that I reject the whole idea of design methods as a subject of study, since I think it is absurd to separate the study of designing from the practice of design. In fact, people who study design methods without also practicing design are almost always frustrated designers who have no sap in them, who have lost, or never had, the urge to shape things. Such a person will never be able to say anything sensible about ‘how’ to shape things either.”

It is this lack of “urge to shape things” that I find most troubling in the modern-day method cards.

We seem to be more focused on pseudo-scientific, quick paths to shallow solutions, rather than a immersive depth of creative craft.

I see this in the cards themselves.

The d.school describes that a good way for designers to become mentally active is to play “Category, category, die!” The instructions in their widely accepted and respected deck directs players to, “Line people up. Name a category (breakfast cereals, vegetables, animals, car manufacturers). Point to each person in rapid succession, skipping around the group. The player has to name something in that category. If she does not, everyone yells ‘die!!’ and that player is out for the round.”

The “video editing” card states that “music is very powerful: use it wisely.” This method is said to “make or break a video.”

The cards explain that a Composite Character Profile “can be a great way to create a ‘guinea pig’ to keep the team moving forward” and that a “Critical Reading Checklist” asks “four basic questions: What’s the point? Who says? What’s new? Who cares?”

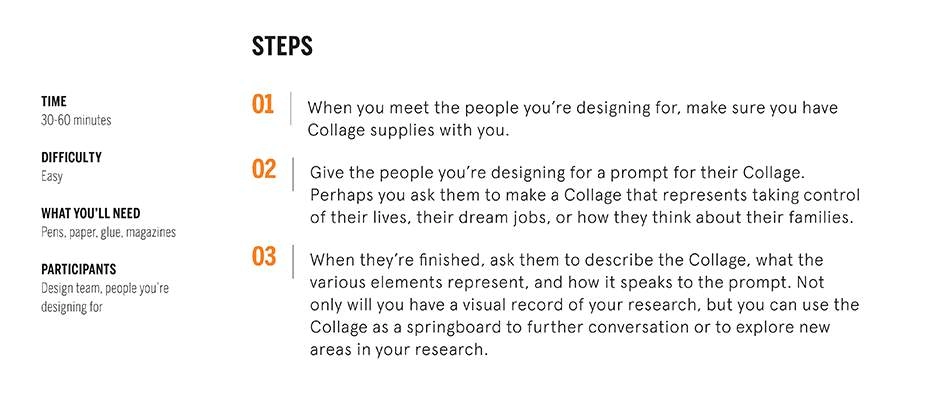

IDEO’s cards are similar–their “Collage” card describes that “Making things is a fantastic way to think things through, one that we use at IDEO.org to unlock creativity and push ourselves to new and innovative places.” The method is as simple as one, two, three:

- When you meet the people you’re designing for, make sure you have collage supplies with you.

- Give the people you’re designing for a prompt for their collage. Perhaps you ask them to make a collage that represents taking control of their lives, their dream jobs, or how they think about their families.

- When they’re finished, ask them to describe the collage, what the various elements represent, and how it speaks to the prompt. Not only will you have a visual record of your research, but you can use the collage as a springboard to further conversation or to explore new areas in your research.

I’m not cherry picking these; most of the methods have a similar approach to creativity. They’re troubling because they’ve positioned themselves as legitimate instructions for “how to do design”–follow the instructions, and you become a designer. It’s that easy.

And lest I sit in my glass house and throw stones, I’m guilty of this too. My second and third books offered methods, the earlier focusing on synthesizing data, and the latter on tackling complex or “wicked” problems. I reduced the value of “things designers do” to a name, a blurb, and a set of steps, because I wanted the material to be easily accessible. In the first case, my goal was that designers would be able to learn new approaches to insert into existing processes. In the second, I was aiming at a broader, more novice audience. Methods seemed like the best way to communicate the power of design in a concise, easily understood way. But this concision ultimately reduces the power of design thinking and strategy.

I think some of the people making the card decks recognize this as well. The deck from IDEO warns that “these cards aren’t meant to be prescriptive nor exhaustive ‘how to’ for a human centered design.” But the cards exist nonetheless, and their rich aesthetic and simple language make them feel like a ‘how to.’ The d.school’s guide comes with no warning, and instead explains that the “methods provide a tangible toolkit” that, along with the other materials in the guide, are “vital attitudes for a design thinker to hold.”

The difficulties with design methods are:

- Methods are watered down instruction, offering only the thinnest description of how design works. It’s not as easy as 1-2-3. It’s a profession that takes time and practice.

- Methods imply that experience doesn’t matter, and that anyone with a card can be a designer. Becoming “good” at design is as arduous as becoming a competent writer and while everyone can benefit from the value of design, it is an art that should be respected and taught with the same broad popularity as literature or philosophy. Experience trumps method every single time.

- Methods are overly prescriptive, indicating that “design should be done like this” and that there is a right and wrong way to go about solving problems. I see this when I teach both graduate students and professionals. They are constantly looking for the optimal to do things, often asking questions as rudimentary as “what size post-it note should we use?”

- And most importantly, methods make design seem scientific, when it is experimental. Design is not just a directed, purposeful activity, it is reflexive, as is much creativity. We lose ourselves in the work, and the work talks back, and out of the creative process emerges magic. This is not a science of the artificial– it is an exploration of the artificial.

I’m concerned that the methods we’re promoting are doing a disservice to the people using the cards. Collaging can help people express their creative ideas and participatory activities are an important part of research, but participatory design is not collaging–it’s tacit knowledge, built on years of experience. Video editing is not a “method,” it’s a profession. The activities that have been boiled down to a method card are really the hard, roll up your sleeves work of practicing designers. “Methods” won’t fix the world’s most difficult problems. Only hard work, perseverance, and a lifetime of experience can drive the real change-making we strive for as designers.