This is from 2018 | 9 minute read

A Key to Growth: Do Something You Suck At

Late last year, I hit a big wall. I ran out of steam and became complacent. I didn't push my professional work - I made things that weren't very good. I didn't try. I was in a funk.

I don't think anyone really noticed, because I'm able to hide it pretty well. I've been a designer for twenty years. I'm pretty good at what I do. I say this not to boast, but to describe the backdrop for this experience - I'm able to do competent work without really being in my element, and that's what happened. I had happy clients, and work that solved the problems it needed to solve. But throughout it, I was completely disengaged. That's not fair, to me, my partners, and my clients. It's not fair to the creative work, either: I've always felt that the work product should be great, or it isn't done.

In the midst of this low, I received some advice from my therapist. She told me to "do something I suck at that has nothing to do with technology" (that's a direct quote). Her suggestion was to find something new that was really, really hard, that I had no experience with, and that I had interest in learning. And this something should have nothing to do with computers or software: it should be tangible and physical. She described that I was at a point in my career where the challenge was disappearing, or - in this case - had disappeared entirely. She called this "expertise" and said I was an expert at my work, and as a consequence, the challenge to grow was gone.

That took me some time to process.

I've never considered myself an expert in anything. I thought that "being an expert" meant you had arrived at the top. But I've always believed that there's no "top" to learning, and particularly in a creative field, there's always an opportunity for progression. Every design, business, and strategy problem is different, every process is unique, and for many of us, that difference is the best part of the job. But the more I thought about it, the more I realized that, language aside, she was right. I had built up a pattern language of problems, approaches, and solutions, and that could be considered "expertise": it was a series of models and templates to execute effectively. Our work is in strategic innovation, and ironically, I had found a way to operationalize innovation.

I've talked this over with a lot of my professional peers and with my friends, and I'm not at all unique in this situation. At around 15 or 20 years in a career, this is a common wall to hit. Colored by boredom, it manifests as "going through the motions." At this stage in a career, many people have prioritized other aspects of their life, like their family, religion, or community, over their work. But most of the people I spoke with still missed the challenge, the excitement of learning. They weren't content with this pseudo-expertise. For some, it lingers the rest of their whole career. It's a low that becomes "just part of the job."

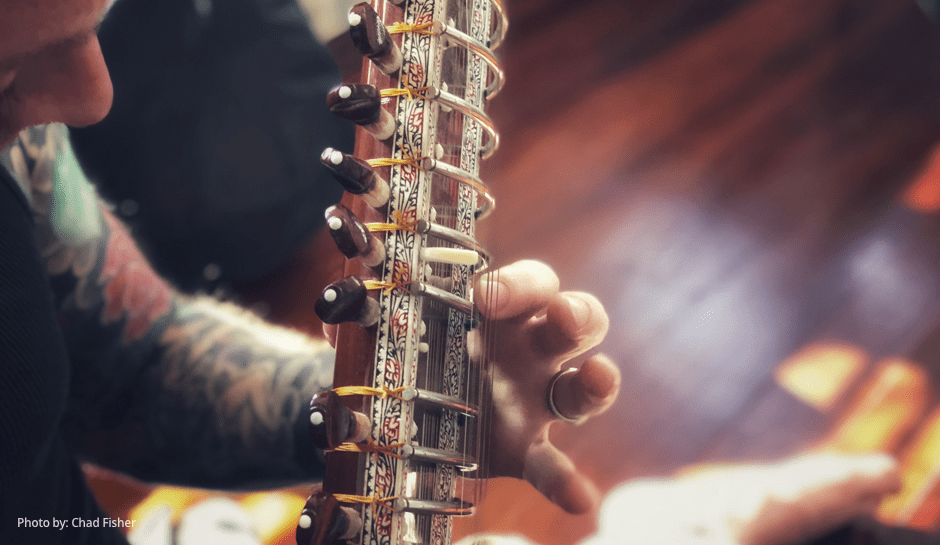

My therapist is really good. So I took her advice. I started playing the sitar.

If you aren't familiar with Indian music, a sitar is a 20 string wooden instrument that bears a very, very vague resemblance to a guitar (it has frets and the player strums it). The music is tonal and based on simple and complex grammars - it can be thought of as improvisational, but built on strict and established patterns. It was popularized in western culture in the sixties, as it was associated with rock and a woodstock-style counterculture: smoke some weed and listen to the mysterious music of another culture. More recently, sitar music has been integrated into ambient techno and other forms of drone-style music.

I grew up listening to Indian music, as one of my art mentors was an avid fan. It's always been a part of my life. So I picked that as my digital-less challenge. I figured - how hard could it be?

It's hard. It's really hard. It's hard to learn to play. And playing it is only one of the complexities. It's actually hard in every way: it's hard to hold, hard to sit properly, hard to engage with the strings (which are made of steel and bronze), hard to read the music, hard to tune, hard to understand the rhythms, hard to find a teacher, and so-on.

When it first arrived, I put it in our spare bedroom and didn't look at it for three weeks. It weighed on my mind, like the telltale heart; "play me, I dare you!"

Eventually, I tried it.

My first interactions with the sitar were at once exasperating, humiliating, humbling, and exciting. I'm stubborn, and I was sure I could figure it out. I watched Youtube videos to learn how to sit, how to hold it, and how to make it make noise. It was terrible. I sounded like a 7 year old playing the violin for music class. My cats ran away and hid under the couch. I gave up.

I tried again the next day. I broke a string and spent two hours figuring out how to replace it.

I realized that I couldn't go it alone. I researched teachers, and found one in Austin, and then I had my first lesson.

Just as my first attempt at playing was humbling, so too was my first sitar lesson. I'm a teacher, but suddenly I was a student. I struggled with the basics, and my teacher was patient. We worked on basic technique, over and over. Through the lesson, in the back of my head the entire time was a reflection on my own teaching - remembering what it's like not to know. A good teacher is able to simultaneously make things challenging and seemingly simple, making something that seems out of reach just barely reachable.

Over the next few months, I became better at the sitar. I stopped scaring the cats, and I got to a place where I can play little sargams related to Raga Yaman Kalyan: small passages that sound vaguely like a larger traditional composition. I saw marked improvement and achievement. But I constantly have this awareness of the size of my challenge. I was at 0, and at 0, it's easy to see getting to 1. But 100 can seem insurmountable. I realized that I could ignore 100, and focus just on incremental progress. And more than that, I slowly stopped worrying about progress at all, and just focused on the joy of the instrument and my joy in playing it, however poorly that playing was.

Learning something new – something that I suck at – has completely rebuilt my confidence in learning, my interest in teaching, and most importantly, my professional work. The energy from my work with the sitar has slipped into my other projects, and I've been motivated to really push my creations. I think there's a few really concrete reasons why this worked.

- I've expanded my own definition of myself. Over the last two decades, I had firmly decided who I was, professionally. Some of that was on purpose, and a lot of it was serendipitous, but all of my experiences had given me a view of what I was about, what I was good at, and how I wanted to perceive myself and to have others perceive of me. This experience has changed that. I don't expect to view myself as a musician, but I am starting to see myself again as someone who is curious to learn, and someone who has things to learn.

- I've found a new attention to detail. Playing an instrument is all about detail. Somehow, in elevating my professional focus to strategy, I've started to lose track of the details of craftsmanship. This experience has sparked my awareness of the unique, small, nuanced details that add up to great design.

- I've become more considered in my actions. Handling an instrument is about respect, and that means being more aware of my physical gestures and actions. Expertise leads to flow, and flow often means disconnecting from awareness. But there's also value in being painstakingly aware of what you are doing while you do it: avoiding the flow state in order to be present with a tool.

Most importantly, I've developed a more relaxed approach to work itself. My sitar playing has been peaceful, even in its challenges. My work hadn't been - it was mostly a brute-force, stubborn approach with a lot of broken glass. My creative style and leadership approach has always been intense and demanding. Now, I'm actively starting to dial the intensity down.

It was important that my challenge was non-digital. The physicality of the sitar - the uncomfortable sitting, the awkward hand placement, the vibrations in my hand, the aching back - all centered my contemplation around the learning. I was distraction free, left only with my emotions and my actions. I couldn't fake my naivety by leaning on my knowledge of the ability to type, or my ability to use a mouse, or my ability to use an operating system or a browser. Everything was completely new, and in that newness, I was able to tear down and build back up my confidence in myself.

This is a key to learning. It’s recognizing that “everything is new” when you are a student, and empathizing with what that newness feels like.

It’s a supportive mentorship that doesn’t water down the difficulty, but is there alongside. And it’s seeing slow and steady progress, visible indicators that learning is occurring. For me, that came through the actual music. For my design students and colleagues, that’s often on me to frame the progress: to help them compare where they are to where they’ve been.

The key to learning and professional growth is to do something you suck at. It feels terrible and wonderful. And it's transformative.

Incidentally, if you are curious to hear what I've been learning, check out Anoushka Shankar playing Raga Yaman Kalyan. The word of this post has been 'humbling'; this video is truly humbling, and mind blowing. And inspirational.